Hey reader,

As promised, this week’s essay is a rundown of my family’s long-term decarbonization action plan, including what we’ve done to this point, where we struggle, and what is to come. I’ve tried to be as specific as possible and have included price points where applicable — if you have any questions about anything discussed here, hit “reply” and I’ll elaborate.

This one is a bit of a doozy, so let’s get right in.

Community shoutouts

Welcome to the 8 new subscribers since last week’s dispatch! You’re here on deep-dive week (I mean, most every week is deep dive week, really) and I hope you take value from this essay.

Thanks to the few of you who shared thoughts on last week’s essay covering what the mainstream media gets wrong about remote work. I particularly loved this comment: “The problem with the mainstream media’s portrayal of digital nomads is the same as its perception of AI: they’re terrified we’re coming for their jobs.”

Now, let’s slash some emissions.

A big-picture GHG reduction plan: Where we’re at

In the first dispatch of 2023, I noted that my family had just purchased an electric vehicle: a 2023 Chevy Bolt EUV. We’d been researching and planning an EV purchase for a few years, and it represented a major step toward our long-term sustainability plan.

This plan is a work in progress, and will likely never be entirely complete. The process of decarbonizing (and . . . de-methaneanizing?) our home and lifestyle as much as reasonably possible has been both a steep learning curve and a very rewarding experience.

Here is our process to date, beginning in early 2014, along with the struggles, analytics, and some notes. For transparency, also included are the primary costs related to each step. It’s important to note that, at current, this process is not cheap. It is wholly unattainable without a middle-class income or higher.

That said, the biggest costs are actually investments rather than spends — both solar panels, e-bikes, and electric vehicles save the buyer money over the long run.

Breaking down our goals

I also want to address the seeming smugness of discussing this topic. I have long felt that the “environmentalist movement” does many things wrong, most notably the perception of an all-or-nothing battle that immediately pits the movement against broader society.

Telling people that they’re wrong and that they must change immediately is never going to work, no matter the topic and no matter the consequence. Throwing buckets of paint or trash on famous paintings is a pathetic attempt for attention and pushes people away from your cause rather than drawing them towards it.

I am not here to preach or intimidate anyone. My objectives in writing this essay are to lay out what my family is doing so that we have it in front of us, and with the hope that someone might find inspiration to take from it and/or confirmation in the value of their own efforts, no matter how small.

I don't see sustainability as an all-or-nothing battle against the establishment. I see it as the inevitable way forward, with technological advances and innovative minds developing, on a rolling basis, new and increasingly more eco-friendly ways of doing things. It’s already happening (I suggest the Keep Cool newsletter from Nick Van Osdol as a great way to keep up to date with exciting developments).

By embracing these advances as much as they can, individuals can do their part to move in the right direction. The result, as I see it, will be a hockey-stick graph in the direction of a better future.

Ok. Onward. The ultimate goal here is to eliminate upwards of 80 percent of our family’s greenhouse gas emissions from 2013 levels. At that time, we lived in a small apartment without renewable energy, drove gas-powered cars on a daily basis, and produced an average amount of trash.

We plan to reduce the impact of each by accomplishing the following:

Transitioning to renewable energy power for our home

Transitioning to electric vehicles and e-bikes/bicycles as our primary forms of transport

Minimizing the impact of our diet

Working towards a Zero Waste lifestyle

Wasteful thinking

Part of living a more sustainable lifestyle stems from small daily habits such as using reusable water bottles and coffee mugs outside of the home and minimizing general trash production.

The reusable bottles are easy to implement, but we’ve gone in waves when it comes to minimizing trash. Overall, there has been immense progress, but our initial goal of “zero waste” implemented in 2016 proved insurmountable. However, the formal Zero Waste movement calls for diverting 90 percent of what one uses from the landfill, and after several years of honing, we are very close to this goal.

A few notable decisions that have helped this process:

Moving to an agricultural area like Palisade from Denver allowed us to greatly reduce the amount of food we purchase from grocery stores during the summer and autumn months. The weekly farmer’s market and local farm stands provide the bulk of our produce, bread, and some other foods during this period. Remote work allowed us to make this transition, and it has resulted in saving a small amount of money.

Recycling, as we’d always done, and biking to work/around as much as we can. My wife was instrumental in leading this charge, becoming a committed bike commuter when working for the City of Lakewood beginning in 2015.

When our daughter was born, we signed up for a cloth diaper service, which delivers a fresh batch of clean diapers each week and picks up the dirties. This service also provides reusable wipes, though we use disposable wipes for large #2s. We also use a disposable diaper for overnights, so as to avoid having to change a diaper every 90 minutes during sleepytime. ($112 per month)

Where we struggle:

I find that most of the trash I produce stems from two primary sources: plastic wrapping/bags on food items and disposables which are provided alongside other purchases (often online ordering). I have tried many times when ordering takeout — something that has increased in frequency since we became parents — to ask for no cutlery or sauce packets, and about 3/4 of the time this request is forgotten or ignored. It seems impossible to avoid plastics when shopping for food and certain other items. I use as much of it as possible to pick up after my dog, but even then, you’re sending plastic waste into the landfill. I would love your tips here if you have any.

Windsourcing for the win

In February 2014, we purchased an 800-square-foot condo in the Denver suburb of Lakewood. This was our first property purchase, and a huge step for us, both financially and in terms of lifestyle.

The condo ran on power from the local utility with a gas furnace and water heater. The local utility, Xcel Energy, offers a program called Windsource that allows residents to opt-in to invest a small amount each month into renewable energy projects, with much of the investment covered by the utility. At the time, the project being financed by Windsource was the development of a wind turbine farm in Wyoming.

While we weren’t necessarily guaranteed wind power delivered to our home right away, the program allowed residents to do their part in the development of the future grid, effectively offsetting part of the emissions of their current energy use.

We joined the program almost immediately after closing on the condo. For a home our size, the program cost us about $8 per month.

We continued to remain a part of the program after our move to Palisade in 2019. Our home here is 1,220 square feet, and the bill is about $13 per month.

Joining the local solar co-op

During the Covid lockdown in April of 2020, I’d often spend late afternoons taking my dog on long, meandering walks around town that’d typically last for 60 minutes or more, simply because there wasn’t anything else to do.

I’d wrap up my workday, put a couple beers into a backpack, and we’d just walk — cutting down streets and alleys we’d never been down, wandering alongside the bank of the Colorado River, or strolling through an eerily empty downtown peering into dark storefronts and peeing on streetlight poles (at least one of us, anyway).

On one such jaunt, I passed by a home with a sign in the yard that read, “Solar United Neighbors: Join the local co-op.” I took a photo of it on my phone and kept walking.

Back home that night, I looked up the co-op and learned that it was in the process of opening its chapter in Mesa County, where I live, and was actively seeking members. Joining — for free — did not obligate you to buy solar panels, though that was of course the ultimate goal.

We joined, spoke with a rep, and within a month had a crew at our house installing panels on the roof. The co-op allowed us to get bulk pricing on the panels and installation, which saved us a couple thousand bucks.

The installation took two days. The process went like this:

Join co-op, receive information about bulk purchasing

Have a sales rep come to the house to scope the project

Connect sales rep with the electric provider to get numbers on our energy use, in order to match the correct number of panels for our home

Installation

One-month waiting period while panels sync with the grid

Harness solar power that is delivered into the grid

In total, eight solar panels and installation cost $9,200. This was reduced to $6,600 after the 30 percent federal tax rebate that was in place at the time. It was very easy to finance, we had a loan from a local credit union approved right away with a $98 monthly payment over a six-year term, which we paid off after the first year using the tax rebate and some money from savings.

After the installation, I was even featured in this hilarious commercial for the co-op that focused as much on my chicken coop as the solar panels:

What I’d do differently/advice:

Current regulations restrict the installer from providing a number of panels that will produce more than 120 percent of your annual power use, as based on the year prior to installation. We had been in the home for exactly one year at this point and had spent a few months of that year traveling, so our projected power use was a bit lower than what we actually needed. This is particularly true given that we now have a third family member and an electric vehicle that we often charge at home. I wish we had two more panels. I encourage any who purchase panels to consider any future changes that may increase their power use.

All eight of our panels face south. This is great during summer and fall, when the bulk of the power is harnessed, but I’d like to have at least two panels facing east or southeast to boost the amount harnessed during winter and spring, which are often cloudier in the afternoon.

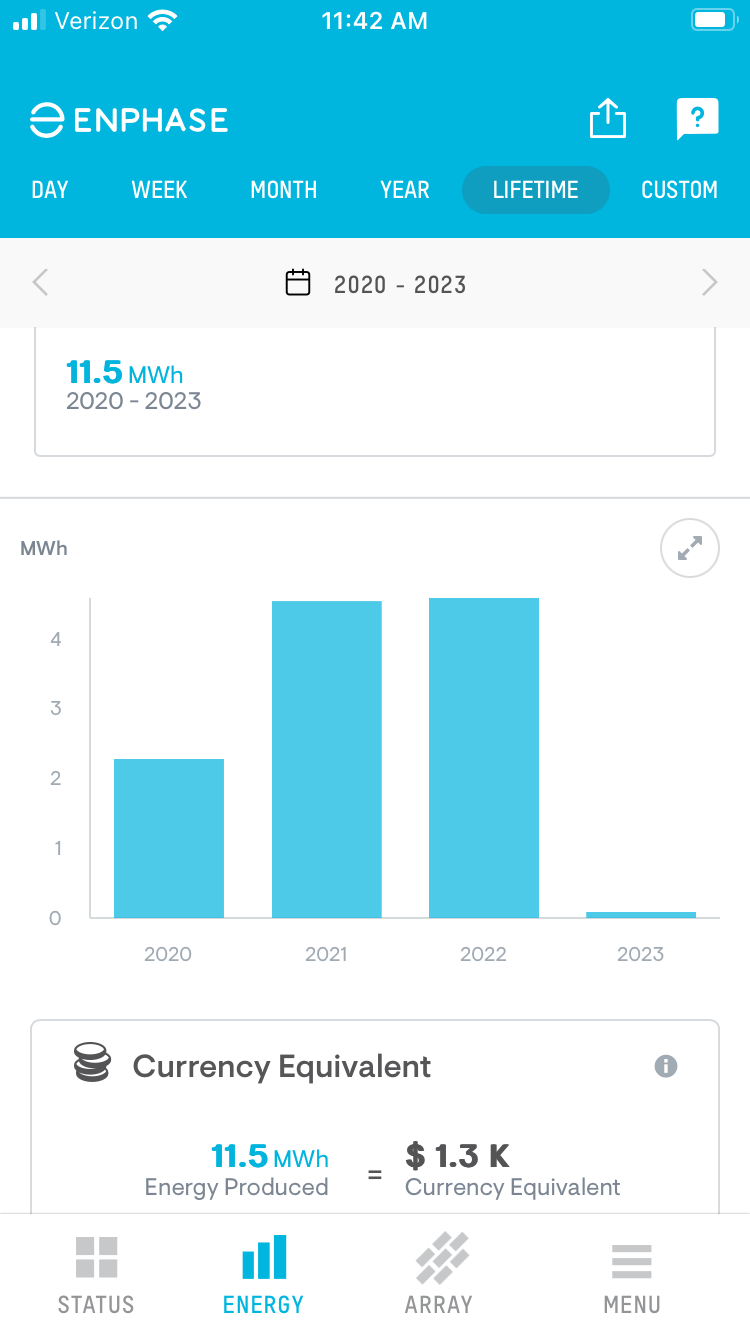

As the screenshot below, taken just now from my Enphase app, shows, we’ve generated 11.5 MWh since the system was installed, knocking $1,300 off our utility bills in the process (and recouping that much towards our $6,600 investment. At this rate, the panels will pay themselves off after about 11 years. If we sell the house before then, the value of the panels and their 25-year warranty is added onto the home price, so we’ll recoup the cost either way.

Buying a ChEVy

For the past four years or so, I have followed the electric vehicle industry closely, thanks in large part to the consistent efforts of publications including Clean Technica, Electrek, and others.

(here is my research folder, for any who’d like to take a look. It’s thin at this point, but there are some helpful articles linked)

My wife and I made the decision a few years ago that the next car we purchased would be an electric vehicle. At the time, our sole vehicle was a 2006 Toyota Tacoma that we shared. We hoped to ride it out for a few years as technology (in particular, battery range and the deployment of charging stations) increased, because we wanted a vehicle that could be both a daily driver and road trip reliable.

Then, in 2021 we learned that my wife was pregnant. Our Tacoma is an access cab with tight bench seats in the back. Great for camping in the bed, horrible for carting around a newborn. We had yet to feel confident in an EV that we could afford and that could serve its intended purpose, and to be honest, our money and focus was on the baby at that point and not on an EV.

We knew we needed a new car, however, and a colleague of Alisha had a 2006 Honda Pilot for sale for a very reasonable price. We caved on our commitment and bought the Pilot, but we swore this would be the last internal combustion engine we’d buy — we’d drive it for a year or two and then make the move, which was likely all the life the Pilot had left in it.

Over the course of 2022, the Chevy Bolt’s reputation — and its amount of press coverage — skyrocketed to the point that for every three or four articles I saw about Tesla, I’d read one that at least mentioned the Bolt and its accompanying crossover, the Bolt EUV. Multiple automotive reporters deemed it the best EV for most people.

I began closely following news on the Bolt EUV last summer. By October, I was convinced this was the best option for us for these reasons:

Its range extended above 200 miles per charge (our Bolt EUV averages 210)

As a crossover, it’s slightly larger than a sedan and has a hatchback with a decent amount of trunk space for outdoor gear. I’ll have to put a rear seat down or get a rack to carry my snowboard, however.

Multiple reports deemed it among the most reliable EVs on the market

Its price point of between $26,000 and $40,000 made it the most affordable of the high-range options

Being an American-made car, it qualifies for the $7,500 federal tax rebate under the Inflation Reduction Act, as well as a Colorado tax rebate of at least $2,000.

It costs about $20 to charge empty-to-full on a public charger, and a bit less than that at home. At a 200-mile range, that’s about 10 miles per dollar. In our Pilot, we got about 6 miles per dollar of gas at 2022 prices, so we’ll be recouping part of our investment over time simply by not buying gas.

Also, there is much less maintenance on an EV, simply because there are far fewer breakable parts. No oil changes, no engine maintenance, etc. This will also help us recoup costs.

A note on the rebate: Although I visited the dealership to put down a $2,000 deposit in November 2022, we waited until January to purchase because the 2023 option was not deemed eligible for the rebate until January 1, 2023, even though it was available earlier. I heard various reasons for this, ranging from “Chevy used up all its rebate credits early in 2022” to “The government still hasn’t decided if the Bolt will qualify due to some issue with its battery production.”

On that note, the car is in high demand, as evidenced by the deposit requirement. Ours was still on the production line when I put the deposit down. This is important to keep in mind if you plan to buy an EV this year — call the dealership or brand you hope to buy in advance to ask about supply, and be ready to put a deposit down and then wait a few months for delivery.

In the end, for whatever reason, the Bolt was deemed eligible for the rebate, at least for now, and we received an eligibility letter from General Motors on the day of purchase that we can submit with our 2023 taxes.

What I’d do differently/advice:

The Bolt EUV does not have all-wheel-drive, which so far is its one drawback. It is front-wheel-drive, at least, so it’s passable in Colorado for most things, but I won’t be driving it to the ski resort in the middle of winter or over mountain passes if there’s a chance of snow.

The Bolt can’t connect to Tesla chargers, which I embarrassingly learned while a Tesla driver sat in his car on a charger behind me as I tried and failed to engage the charger with my car.

To date, we have not had any issues charging. My coworking space has multiple Level 2 chargers available, and as I write this, electricians are installing a Level 2 charger in my garage. GM covers $1,000 of the installation cost if you purchase a new EV this year, meaning we’re only on the hook for about $750.

We opted for some bells and whistles on our car, partly because this specific vehicle was what was available for purchase, and I bought an extended warranty on the battery for an additional $3,000, because you never know . . . . As such, the total came to just over $40,000 — significantly more than the $30,000 I was hoping to pay. But the rebates knock nearly $10,000 off, so it equals out in the end.

The OnStar package includes WiFi service pulled from 4G networks — so you can literally work in the car (as long as someone else is driving, of course). I took a Zoom call while on the road last week and had no connection issues.

I always said I would never buy a brand-new car, because it is, in general, a terrible investment, and there are plenty of used cars available for far cheaper. I broke the rule solely for the purpose of making the transition to an EV — a part of me is not happy about this. We could have bought a used Nissan Leaf and held out for a couple of years until the Bolt EUV was available on the resale market. But I am encouraged by the fact that the burgeoning number of EVs being sold on an annual basis, coupled with newer and better models coming out each year, will ensure a healthy used market for EVs at some point in the foreseeable future.

All The Small Things

Of course, moving down the path of decarbonization isn’t just about the major purchases. Along the way we’ve enacted some smaller things that help with the day-to-day:

Two years ago I obtained a Jackery solar generator with four accompanying solar panels. This is great for camping, and can be used for some household appliances in the event of a blackout.

In anticipation of a splitboarding expedition I’m embarking on in February, I obtained a pair of Goal Zero Sherpa power banks. These can be charged off the Jackery generator and are excellent for keeping devices powered while traveling and while in the backcountry.

Alisha and I have consistently strived to keep it small — we live in a 1,200-square-foot house built in 1900, that is within walking or biking distance of most of the things we need on a daily basis. We do our best to shop locally for food, eat a mostly plant-based diet, and support businesses that take action to address their carbon footprint. I find these things to be the most important for us, because it eliminates many car trips that we’d been guilty of taking when we lived in the suburbs of Denver. My hope is that in the coming years, we’ll be able to return to being a one-car household. In the meantime, I do my best to leave the truck parked most days of the week.

Where we go from here

To date, our family has committed some $50,000 towards reducing our greenhouse gas emissions. Much of this is still left to pay as we work through the car loan on our EV (another thing I said I would never do: have another car loan).

There is much work left to do, including installing an electric heat pump to replace our gas furnace, likely a few years down the road for us, and installing a convection stove and range to replace our gas range, which we hope to do this summer.

I also hope to add a battery pack (maybe even a Tesla Powerwall) and two additional solar panels, effectively turning our home into a power plant that can both produce and store energy. Though the electrician installing our Level 2 charger just informed me that with the charger and solar volatic system, we are running out of breakers, so we’ll have to address that issue first.

I plan to update this article in the future as I have more to add and more insight to share.

In the meantime, please share your tips and strategies for decarbonization. I’d love to hear them, and am happy to share them here if you’d like.

See you next week!

Mountain Remote news and further reading

After years of research and planning, this article from Clean Technica is what sealed the deal for me on the Bolt EUV.

Considering going solar? Take this quiz to determine how many panels you need.

We close this week with an encouraging note on internet service for remote workers who, like me, spend much of their time away from big cities: Nomad Internet provides excellent an reliable internet in rural areas.

Have a great weekend.

Very interesting and informative Tim.

I admire your commitment and follow through! Of course, Alisha’s as well, since this is a partnership commitment.

How do you make decisions around travel and its significant environmental impact? How do you balance the joys and learning of travel with awareness of its negative impacts?